Mastering Maintenance with a CMMS: Features, Benefits, and Best Practices

At a time when the proper functioning of assets is a major concern for any organization, maintenance has become a strategic activity. To address this effectively, it is essential to choose and implement a CMMS software that is both efficient, reliable, and easy to use.

What is a CMMS?

Definition of a CMMS

The CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) is a software tool that allows maintenance teams to plan, manage, monitor and optimize their maintenance and repair operations. These interventions must then be carried out on assets of various kinds: equipment, installations, buildings, networks, linear infrastructure, etc.).

CMMS software is a business solution that supports maintenance/operations teams on a daily basis in their activities, from handling incident reports to managing planned interventions and managing spare parts stocks.

Used by all types of businesses and for all types of goods, CMMS software always serves the same purpose: maintaining assets in operational condition.

History of the CMMS

Maintenance did not wait for the advent of computers to exist and for a long time relied on paper, with maintenance sheets describing the interventions carried out on a machine or infrastructure.

Towards the end of the 1990s, these physical files and records were gradually replaced by spreadsheets: these were the first steps of computerized maintenance.

During the 2000s, CMMS software became more widespread at the same pace as the Internet and benefited from the mobility offered by this network.

Today, computerized maintenance management tools are used by many companies and services, regardless of their size. These software programs now benefit from all the latest technologies, from cloud hosting to artificial intelligence, including IoT (use of sensors).

Types of Maintenance Interventions That Can Be Managed in a CMMS

As the true conductor of maintenance teams, CMMS software manages different types of maintenance and intervention:

Corrective maintenance:

This involves managing troubleshooting following a confirmed breakdown, whether it is curative (durable repair) or palliative (temporary solution).

Preventive maintenance:

This proactive approach aims to prevent breakdowns. It consists of:

- Systematic: interventions planned at regular intervals (e.g., every year).

- Conditional: triggered according to predefined thresholds on key parameters (temperature, vibrations, etc.) representative of the actual state of the equipment. Often based on IoT sensors, it can also be triggered according to manual meter readings, particularly during inspections and rounds (e.g., if temperature >50°C, after 50,000 km, etc.).

Predictive Maintenance:

Based on statistical analysis and AI, this method anticipates breakdowns before they occur by detecting warning signs.

Improved Maintenance:

Although debated among experts, CMMS systems can also manage improvement-focused operations aimed at enhancing ease of use, safety, or performance.

Maintenance Complexity and Expertise Levels

In practice, maintenance tasks can also be categorized by complexity and required expertise. This helps organizations allocate the right resources:

- Basic Maintenance: simple tasks like inspections, cleaning, and lubrication that can be performed by operators.

- Routine Maintenance: scheduled preventive tasks requiring trained technicians.

- Skilled Maintenance: advanced diagnostics, adjustments, and repairs performed by experienced technicians.

- Major Maintenance: large-scale overhauls or upgrades requiring specialized teams and heavy equipment.

- Capital or Rebuild Maintenance: complete equipment refurbishment or replacement, often handled by OEMs or specialized service providers.

Key Features of a CMMS Tool

Asset and Technical Heritage Library

This feature allows you to centralize and track the complete history, location, and costs associated with all equipment and facilities. It provides a detailed view of the performance and condition of each asset to optimize their lifecycle.

Requests for Intervention (RI) and Ticketing.

This allows operators to access a simplified portal. It enables them to create, track, and manage the complete lifecycle of requests for intervention, from their submission until the work order is closed. It serves as a detailed roadmap for the execution of the task.

Preventive Work Schedules and Orders

Preventive maintenance management is based on maintenance schedules that detail the tasks to be performed, the operating procedures, the frequencies (systematic) and/or activation conditions (conditional). These schedules automate the planning of work orders as well as their conditional triggering.

Intervention and External Reports

This system allows for the storage of the intervention report from the external company involved, or provides options for documenting the internal intervention. This includes the recording of key dates, captured photos/videos/audio recordings, and a written report prepared by the intervention team. Ultimately, this information can be extracted into a secure, uneditable PDF report.

Planning and Workload Management

It facilitates the planning of preventive and corrective maintenance tasks, ensuring optimal allocation of human resources. It allows for anticipating planned/preventive interventions and visualizing the workload of technicians based on their skills and availability.

Stocks, Inventories and Restocking

This function ensures precise control of spare parts and consumables required for maintenance interventions. It helps optimize stock levels, reserve parts for scheduled interventions, automate replenishment, and reduce costs associated with overstocking or stockouts. This quantitative management system facilitates inventory counts using barcodes and QR codes.

Connectivity and Interoperability

To be effective, CMMS software must integrate seamlessly with the information systems of the company, such as the ERP for example. Similarly, the CMMS tool can be directly connected to assets via various sensors and other IoT (Internet of Things) technologies.

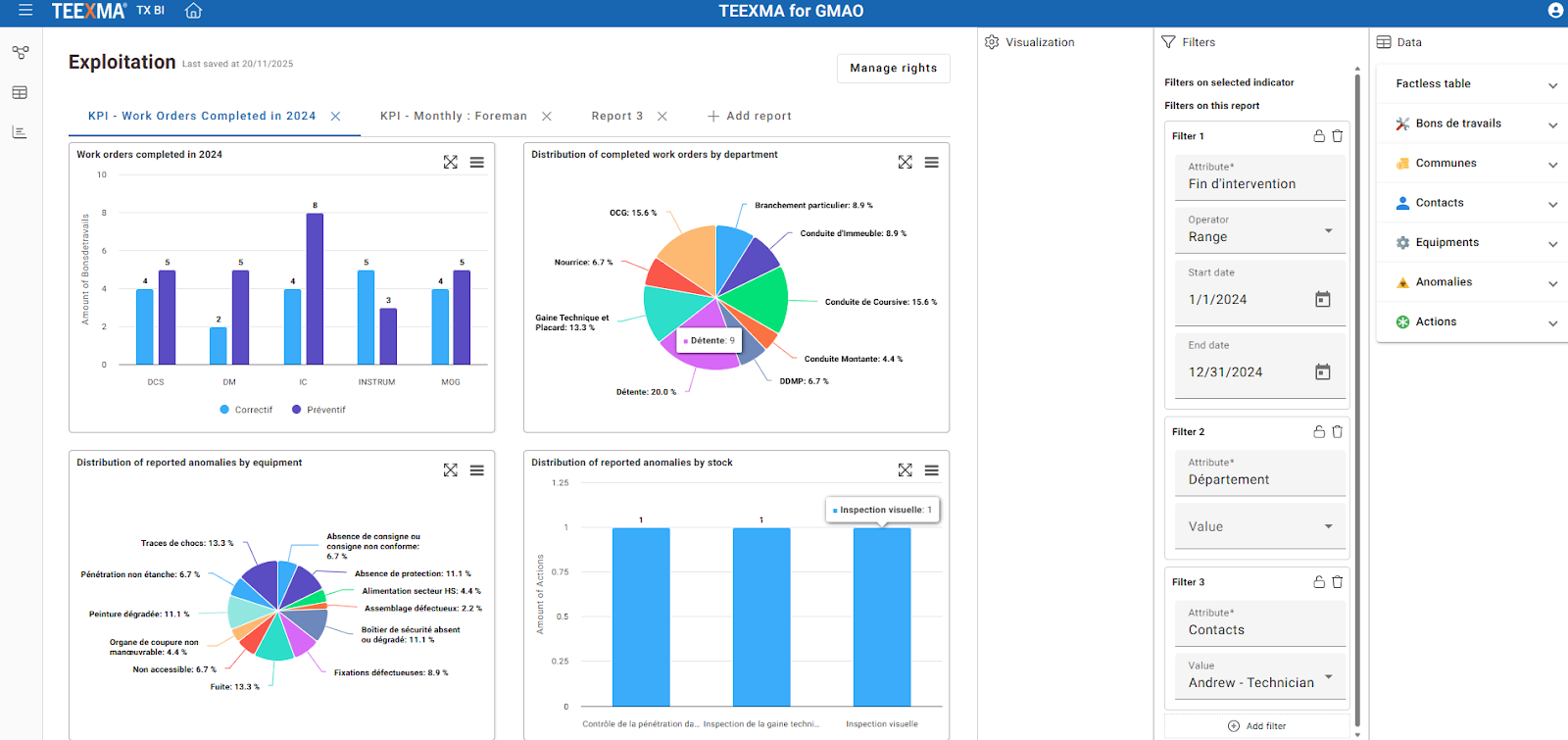

Real-time Dashboards and KPIs

This feature provides a clear visualization of key maintenance performance indicators (KPIs), such as MTTR (Mean Time To Repair) or equipment availability rate. It helps maintenance managers analyze performance and drive continuous improvement.

Example of a dashboard of a CMMS software

Mobile Application

The interventions, the travel, and the mobility are at the heart of maintenance operations. Maintenance software must therefore be able to track technicians during their tours and interventions. From a mobile portal, they gain access to intervention information, equipment history, related documentation, etc.

What types of assets are managed by a CMMS?

A CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) is compatible with a wide variety of physical assets, covering all the assets managed by a company or public service. This range of assets can be divided into major categories:

- Infrastructure/Real Estate: Sites, bridges, dams, buildings, halls, rooms, premises, etc.

- Networks and linear systems: railways, roads, gas, etc.

- Energy: Air conditioning, electricity, water, etc.

- Fleets: Trucks, cars, buses, trains, planes, subways, etc.

- Machines: production, testing, etc.

- Measurement methods: thermometers, calipers, etc.

- Street furniture: bus shelters, streetlights, bins, signs, etc.

- Office furniture: desks, chairs, tables, etc.

- Informational Materials: computers, printers, patch panels, etc.

- Tools: compressors, drills, etc.

- Safety equipment: Fire extinguishers, emergency telephones, signage, etc.

- Green spaces: parks, lawns, forests, trees, various plants, etc.

Professions and Departments Using CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) software

Technical and maintenance service

Whether industrial or institutional, these organizations have dedicated maintenance departments that may have various names, although the main ones are maintenance departments and technical services. They ensure the operational maintenance of the equipment and installations under their responsibility, either to guarantee the availability of the machinery used for industrial production or to monitor the interventions of the personnel involved.

Facility Management and Asset Management

Facility Management (FM), or the management of facilities and buildings, encompasses all the services and assets related to an organization’s workspaces and buildings to support its operations. Assets include the buildings themselves, as well as heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), lighting, fire safety, and grounds maintenance. Asset management extends this management to all assets owned or used by the organization, including contractual and administrative oversight (premises, land, etc.).

Fleet Management

Fleet management is dedicated to optimizing the management of vehicles owned (purchased or leased) by an organization. Its scope is vast, covering all modes of transport (land, air, and sea), and therefore including everything from company cars and delivery trucks to construction equipment, transport buses, and even aircraft. In addition to vehicle management, the management of internal workshops and external partner garages is essential, as is tracking service history and vehicle acquisition contracts.

IT Asset Management

IT Asset Management (ITAM) is distinguished by the management of both physical (hardware) and virtual (software) assets, all crucial to an organization’s operations. ITAM covers physical assets such as servers, computers, and peripherals, as well as intangible assets (software), which include software licenses and operating systems. Therefore, expectations focus on ticketing, cataloging physical and COTS/OOS assets, maintaining asset security through vulnerability monitoring, managing software upgrades, and more.

After-sales service and field interventions (Field Service management)

Unlike the previously mentioned professions, this one concerns companies working on-site at their own clients’ premises and using a CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) to track field interventions. Therefore, the operation is different, with expectations regarding client databases, the creation of quotes and invoices, intervention scheduling taking travel times into account, client access to their online account, and the generation of reports for clients.

Business Sectors Using CMMS Software

Computerized maintenance management software covers a wide range of assets, making it an essential tool for many types of businesses and sectors defined below. Each sector can then integrate one or more of the aforementioned functions (maintenance and facility management, for example).

Industries:

Industrial maintenance guarantees performance and maximizes the availability of production tools through preventive maintenance planning and agile corrective maintenance management.

Transport and logistics:

Crucial for maintaining operations, CMMS is used for fleet management. It primarily allows for the planning of vehicle maintenance (trucks, trains, buses) to minimize downtime and ensure safety.

Energy:

In this highly critical sector, Computerized Maintenance Management is essential for the reliability of networks and production facilities (power plants, wind turbines, dams). It guarantees continuity of service by enabling regulatory compliance to be demonstrated to the authorities.

Public sector and local authorities:

CMMS software is essential for managing public assets and ensures the monitoring and maintenance of assets belonging to local authorities or other public institutions.

Real estate:

Computer-aided maintenance management tools centralize the technical management of buildings, whether residential, commercial, or social. They facilitate the management of maintenance contracts, the tracking of interventions on HVAC equipment or elevators, and regulatory compliance.

Health and hospital:

The use of CMMS software is vital for this sector; it ensures the proper functioning of technical and biomedical equipment (imaging, ventilators, etc.).

Service providers:

For companies that provide on-site customer support, a CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) solution is a true business tool for managing customer contracts. It allows them to manage service calls, optimize technician routes, and generate invoices.

These service providers are varied and are generally divided between specialists in heavy and regulated equipment (lift technicians, fire safety, or HVAC technicians) and multi-technical tradespeople covering emergencies and routine repairs (plumbers, locksmiths, heating engineers).

Benefits of a CMMS for Maintenance Departments

Implementing computer-aided maintenance management is not limited to the digitalization of processes; it generates tangible benefits that transform the maintenance department into a true center of added value for the company.

Cost reduction and productivity optimization

Computerized Maintenance Management is a powerful driver of economic and operational efficiency for the maintenance department. It minimizes unforeseen expenses by promoting preventive and predictive maintenance, thereby reducing unplanned production downtime and the high costs of emergency repairs.

It also ensures complete control over spare parts inventory, preventing costly overstocking and disruptive stockouts. By automating administrative management and information retrieval, the solution frees staff from low-value tasks, allowing them to focus on their core business for significant productivity gains.

Improved equipment availability and reliability

One of the most direct and important benefits of CMMS is improved equipment availability and reliability. Through effective planning of scheduled and unscheduled interventions, it ensures better management of time and resources.

It also contributes to extending the lifespan of equipment through proactive and predictive maintenance, anticipating failures and preventing premature wear.

Finally, CMMS reduces unplanned breakdowns and downtime, thereby maximizing production capacity and asset profitability.

Facilitating the collection and sharing of field information

By using CMMS software directly from their mobile devices, technicians can instantly enter service reports, measurements, anomalies, or meter readings right at the work site. This ensures perfect traceability and high reliability of information.

This real-time information sharing not only enables better collaboration between teams (maintenance, production, inventory), but also feeds into the historical asset database. This wealth of information is essential for analyzing the root causes of breakdowns and for continuously adjusting maintenance strategies (shifting from corrective to preventive or predictive maintenance).

How to Choose a CMMS Software

There are several factors to consider when choosing a CMMS software.

Standard or custom software

The organization must first determine the flexibility it needs. Standard CMMS software is preferred for its low cost and rapid deployment, but is only suitable for traditional maintenance processes. Conversely, a custom CMMS solution represents a longer and more expensive deployment but ensures the organization has a solution tailored to its specific needs and maintenance processes.

Between the two, modular CMMS solutions position themselves as the best compromise. They offer organizations the customization necessary to adapt to their specific processes, while avoiding the prohibitive costs and excessively long deployments of fully custom solutions.

On-Premise or Cloud Deployment

The choice of deployment architecture is fundamental. The SaaS model dominates today: it offers easy accessibility, automatic updates, and a low initial cost through a subscription. The on-premise option, where the software is installed on the company’s servers, is generally reserved for organizations with extremely stringent security and data control requirements or isolated infrastructures.

Developer or integrator partner

When choosing a CMMS solution, companies will encounter two main types of players: software vendors who design and develop the CMMS software, and integrators who are responsible for its deployment and configuration within the company. However, a third type of player positions itself as both vendor and integrator. This approach simplifies the value chain, ensures better technical consistency between the product and its installation, reduces implementation time, and, above all, lowers the overall cost by eliminating intermediaries.

Cost

Maintenance is often perceived as a cost center rather than an investment. Understanding the true cost of a CMMS solution is therefore essential. The price of the software alone is insufficient, and a rigorous analysis of the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is essential. This cost must include not only user licenses, but also all recurring expenses such as updates, team training, and integration costs with other systems.

Note: There is no free CMMS software. Some companies may be tempted to use Excel spreadsheets to manage their maintenance. This manual approach quickly reaches its limits, as it offers neither the traceability, nor the centralization, nor the planning functions required for modern and efficient maintenance management.

Integration and connectivity

Computerized maintenance management software is central to an organization’s IT system and must be able to communicate with other tools to function effectively. It is essential to assess the software’s ability to interface with the organization’s IT system, from ERP systems and IoT solutions to Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

Mobility

The end users of CMMS software are maintenance technicians. If they are in the field, the solution must be able to track their daily activities and movements, even offline. This makes mobility a crucial option to enable.

Support and training

As with any technology investment, the key to the success of a CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) lies in its optimal adoption and use by teams. It is therefore crucial to verify that the vendor offers a comprehensive training plan to fully utilize all the solution’s functionalities, as well as responsive and readily available technical support capable of ensuring operational continuity in case of difficulties.

Ergonomics

Directly linked to adoption, ergonomics and User Experience (UX) are paramount. It is imperative that the software displays a simple and efficient interface. This ease of use guarantees that the equipment maintenance teams will quickly integrate the tool into their daily practices, ensuring the success of the deployment.

Difference between CMMS and EAM

The evolution of maintenance has given rise to broader concepts, including Enterprise Asset Management (EAM), often described as a “CMMS++”. It is important to understand the nuance between these two to better position the solutions in the market.

While computer-aided maintenance management focuses primarily on maintenance interventions and equipment tracking, EAM is centered on the comprehensive management of the asset lifecycle. This means that EAM encompasses much more than simple maintenance. It includes crucial complementary dimensions for optimal asset management:

- Operational: monitoring of construction sites and works, integration of metrology, monitoring of qualifications.

- Administrative: Integrated document management, contract monitoring, subcontractor management, warranty management.

- Financial: Preparing quotes, managing invoicing, calculating asset ownership costs, and monitoring budgets.

- Staff safety: authorization management, work permit monitoring, safety procedures, prevention plans, lockouts/tagouts, etc.

- Logistics: multi-store management, spare parts supply, obsolescence and securing of supplies, identification of dead stock and optimization of possible stocks, etc.

A solution like TEEXMA for Maintenance is a true EAM (Enterprise Asset Management) system. It offers full management of maintenance activities, going far beyond the traditional functionalities of a CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System). However, its modular nature allows it to be used as a CMMS depending on the client’s context, by activating only the necessary modules. This flexibility makes it a suitable solution for a wide variety of needs and company sizes.

The Role of IoT in Predictive Maintenance

The Internet of Things (IoT) has truly transformed the way businesses collect and use data in the field. With the help of sensors and monitoring tools, it is now possible to retrieve operational data in real time. This information may include operating time, alarms, usage counters, temperature, vibration, and much more.

This live data is invaluable because it allows the creation of automated interventions that closely mirror the actual degradation of equipment. When the collected signals reach predefined limits, condition-based preventive maintenance is automatically triggered. This means that breakdowns are avoided by intervening at the precise moment needed, just before a failure occurs. This allows for the optimization of maintenance strategy and costs both directly and indirectly. Thanks to this volume of data, it is also possible to reassess historical choices and manufacturer recommendations based on the actual use of the equipment by the customer (for example, increasing the frequency of routine preventive maintenance).

Furthermore, the use of aggregated data (historical data on preventive maintenance, breakdowns, etc.) helps determine MTTR (Mean Time To Repair, and MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures). By analyzing these datasets, companies can optimize their existing maintenance plans and predictively anticipate breakdowns by identifying hidden patterns and correlations. The integration of IoT and data analytics paves the way for smarter, more proactive maintenance.

How is Artificial Intelligence Transforming CMMS?

Artificial intelligence is no longer an experimental novelty, it is already transforming the daily operations of maintenance services. Through various functionalities, AI assists maintenance technician teams with several challenges:

Problem anticipation/prediction:

AI analyzes historical and real-time data (from sensors) to identify early warning signs of potential failure. This allows for proactive intervention, often before technicians even detect a problem.

Planning optimization:

Thanks to the computing power of AI, it is now possible to generate optimized schedules in seconds. This scheduling is based on business constraints such as availability, priority, deadlines, etc.

Virtual assistant and chatbot:

The use of chatbots and virtual assistants improves the user experience and simplifies complex searches within the system. By asking questions in natural language, the chatbot responds based on your organization’s data, thus facilitating the search for similar cases or information within the system.

Transforming documents into usable data:

AI makes it possible to unlock the potential of the data contained in your documents. Digitizing external reports, creating product ranges based on manufacturer manuals, etc., are all examples of applications of this technology that facilitate the use of data previously stored for traceability purposes.

Are you a maintenance manager looking for more information about CMMS software?

Talk to one of our maintenance experts or schedule a demonstration of TEEXMA for Maintenance directly. Its unique modular approach offers businesses and communities a tailored and flexible solution, without the costs and complexity of full development.